A few months later, the advisory committee would return to Athens, Georgia transporting multiple film projectors, slide projectors, reels of audio tape, bottles of synthetic smells, and exhibitions materials. All this equipment was required to present, “A Rough Sketch for Sample Lesson for a Hypothetical Course, “as Charles would call their work. Meanwhile, Nelson had already given their project its simple yet provocative title: “Art X.” By any name, the demonstration wowed audiences of the UGA faculty and members of the public. The result of the Nelson-Eames demonstration exceeded Lamar Dodd’s original hopes for the committee and provided his school with a working model for future teaching curricula. While a New York Times reporter published a rave review, the staff of the University of Georgia immediately reevaluated their plan for the fall semester. A designer, who had recently obtained his doctorate under Hoyt Sherman, would lead the charge, Dr. Erwin M. Breithaupt Jr. The faculty tore down walls between classes to produce a suitable freshman course load even though they would only have a summer to compose their new automated multimedia lessons.

In 1951, an advisory committee was proposed with George Nelson and Charles Eames as permanent members with a third member to be appointed by the two men. In November of 1952, they returned and proposed a project for the spring of that same year.

“These proposals dealt with the presentation of information, and knowledge that have direct relationship to basic courses in design and art appreciation as well as the more advanced areas of concentration.” With the plan that visual aids would be used in different ways, a meeting was held in winter of 1953 to demonstrate the technique. “These demonstrations were to include every possible aid by which material, information, and knowledge could be presented to students in the shortest possible time....” (This and other quotes comes as recorded in the materials compiled in the Academic Reports of The University of Georgia, in the respective years if not specifically mentioned.)

When Lamar Dodd called George Nelson he asked him to visit Athens and discuss his thoughts about teaching, it began like so many school visits; like so many other lectures. Nelson did, in fact, address the commercial art classes which were in the process of growing into a graphic design program. Nelson also studied the work the students were doing and the teaching the instructors were doing before calling a meeting with the staff.

In Nelson’s opinion the discussion was expertly moderated by Lamar Dodd, who appeared to be casually questioning everything the school had ever done or hoped to do. Simply put, the debate was heated, with instructors on all levels of tenure worried about their jobs and the sanctity of their profession. Nelson observed that there was redundancy in almost all classes in all lessons. He noted that there was a confused focus as to what was being taught at any given moment, on both the part of the students and teachers.

Nelson concluded that many students had no real aspirations in the field of art making, but the current curriculum required them to pretend they would be professional artists. In the din of shouting and accusations, Nelson claimed that a more collaborative and comprehensive program should be created, one that used the modern methods of industry such as film. Charles proposal included saving money by replacing all but the most talented of teachers and using these automated lessons to help teach more students with less instructors. Teachers were not pleased as one might imagine.

The conversation between Lamar Dodd’s faculty and Nelson, their consultant, resolved only that more research needed to be conducted. This led to the creation of an advisory board which would include Nelson, and two other experts.

With Nelson’s help Dodd persuaded Charles Eames joined them in Athens, Georgia to continue the investigation. More studying of teaching at Georiga by the new member led to similar conclusions. Sensing uncomfortable changes ahead, the staff voiced concerns that they were meant to become the slaves of time motion studies. They refused to be dictated on how to teach, and they doubted it was even possible to teach in the way Nelson and Eames wished.

So, the newly appointed advisory board was obliged to provide an example.

“It was to deal with the problem of creative teaching, and all emphasis was placed on the most effective teaching methods that might be embodied and all efforts related to new and better ways of presenting significant material.”

With the final addition of Alexander Girard to the team of experts, the Advisory Board would begin production on an actual working example of how to execute modern teaching.

Nelson and Eames agreed to split an hour long lesson while Girard provided the companion materials: posters and exhibits. For months the men compiled motion film, photographic slides, drawings, diagrams, and concepts from popular culture, science, music.

They resolved to design a system using the projection three screens. This simple idea allowed the designers to make their product easy to transport and set up, with the added bonus of allowing multiple images to project simultaneously. As word spread of the scope and intentions of Eames and Nelson’s project, the public’s imagination was sparked. There was a palpable sense of anticipation for the future in America in the early Nineteen Fifties, which gave modernizing of a fledging art school a great sense of purpose. CBS Studios offered the free use of their equipment for filming, while the Eames’ private studio heavily invested their own money and resources as well.

The product arrived packaged up in boxes, to Athens, Georgia in the winter of 1953. The presentation was still a work in progress and its debut would be the first time the designers would see each others sections of the show. During its inaugural run they realized they would need eight people to help run each demonstration.

The scope and scale of the demonstrations fully exceeded expectations and although the demonstration was not planned for the public, there were 9 audiences of 1,000 people each.

“Representative from many schools through the SE and the North, East, and West were present. (One of the art critics of the NEW YORK TIMES was here for a two-day period, and the following appeared in the TIMES: “The University of Georgia…. Recently presented a premiere of a challenging, pioneering approach….using movies, triple slide projectors, sounds, smells, an exhibition.”

“The demonstration is difficult to describe. The only way that any of you could understand the experience we had would be for you actually to witness it yourselves. I considered bringing with me a portion of this experiment, but a portion would not have done the project justice,” Lamar Dodd explained at a later conference of educators.

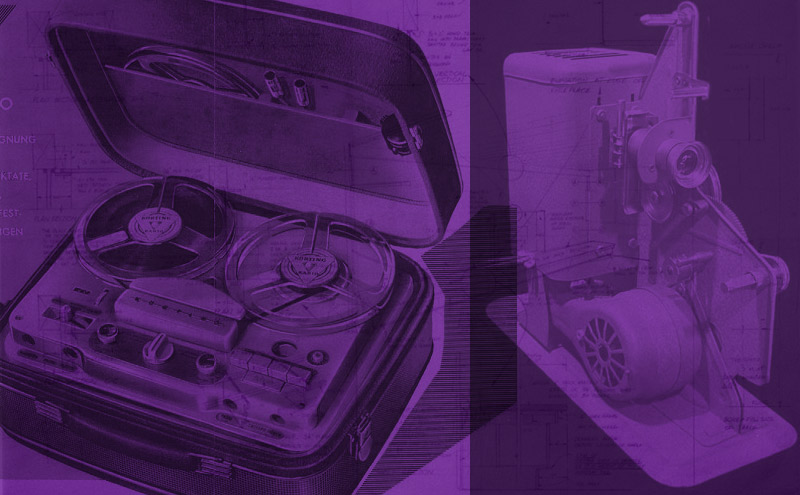

Imagine a room sixty five feet in length and thirty feet wide. “The room is equipped into three 35-mm projectors; one movie projector, tape recorders; tape recorders; amplifiers; microphone and speakers; fans and one large stationary movie screen flanked on either side by a screen for slides. In all, nine people were used in the operation of the projectors and equipment. The walls were covered with reproductions of the frescoes of Giotto; enlargements showing the Benday process; circus posters; road signs; large white pieces of paper; black strips; a red numeral “5”; and other examples that deal with the subjects of communication and art. The experiment itself was entitled “Art X”, but the subject was communication."

These are notes from George Nelson’s report on Art X come below:

-Excerpts from a French film, “La Lettre,” on the evolution of lettering and calligraphy were used, it was shot in 16 mm black and white film, and it lasted 4 minutes.

-A demonstration on the subject of abstraction in communication changes from single slides to simultaneous triple projections shown below. Smell effects (incense) accompanied slides of cathedral interiors. 35 mm color slides projected with a Running time, 8 minutes as presented by Nelson.

-Film gave way to a triple slide sequences, simultaneously projected. The sequences (about 50 in total) cover and the variety of types of visual communications: painting, artifacts, sculpture, equipment, landscape design, structures, type faces, etcetera.

-The intention is to show that comprehension of a message varies with the capacity of receiver. A musical background, no narration. Running time, about 10 minutes, designed by Nelson.

-The process of communication is shown as it takes place between two people (“I Love you”) between artist and audience, etcetera. Running time: 10 minutes. By Eames.

-Communications Process

Picks up the opening idea of the transmitter message receiver relationship and develops it.

-There is the example of a stockbroker’s office, with transmissions of the simplest message: “Buy” or “Sell.”

-“Noise” is described as a factor in message distortion.

-The point: The use of abstraction is necessary in communications, since it is rarely possible to send a total message. Examples: a Picasso still life, maps of a section of London (“change the information and you change the picture”) and cathedrals in England and France.

-Opening film (ten minutes) makes one point: the completion of a communication requires not only a message and a transmitter, but a receiver capable of tuning in.

-Message: song from “Guys and Dolls”

-“Receivers” include student in American history (not used to thinking of Paul Revere as a horse). Constructed in the form of a fugue. Bookie, who knows all about race horses, nothing about fugues, specialist in oriental literature, who does not speak English. Each can receive only a portion of the apparently simple message.

-Example of ways messages may be broken individual decisions: half tone photograph of a face is made up of several hundred thousand black-or-white decisions.

-An electronic computer presents as many possible decisions as the half tone.

“The simples human act” – picking a flower- takes infinitely more stop-go decisions than the most complex computer or printing plate.

-Mosaic and pontilliste paintings are examples of complex productions visibly based on great numbers of separate, decisive acts.

-These fragmentary overviews of the films, are scripts in reverse. Used to describe the show after the event.

This script is part what Charles called, “A Rough Sketch of a Sample Lesson for a Hypothetical Course” his title for the show George Nelson called, “Art X." He continued perfecting this sample lesson through different formats, venues, and for different clients.

(Note: Both the “Process” and “Method” films, by Eames, have been merged into a single 16 mm color films., which runs about 20 minutes, entitled “A Communications Primer.”)

Having provided excerpts from notes above, here follows a more descriptive narrative of the experience from various accounts, including Lamar Dodd and the staff of the University of Georgia’s art faculty.

After Mr. Nelson made a few introductory remarks, explaining the purpose of the experimental demonstration, a color sound movie was projected on the center screen. Colored oil paints were squeezed from tubes and applied to a flat surface, spelling out the title of the demonstration, “Art X”. Then one was instantly introduced to numerous symbols and ideas dealing with communication. The film showed Times Square at night, with all its electric lights, its color, its gaiety, we saw “Guys and Dolls” on a theatre marquee’s sign and viewed a song sequence from that Broadway show—a song about a horse named Paul Revere; next we were watching and hearing a man play a Bach fugue on a magnificent pipe organ, and we were suddenly aware of the fact that a fugue was also the theme of the song from the gaudy “Guys and Dolls” musical comedy.

The movie would stop, to be replaced by quick series of three slides shown simultaneously. Words would replace music, and sounds would replace symbols. Throughout the performance, the observer was conscious of a great wealth of material, even though at times it seemed unrelated; Africa; Ancient Egypt in all its glory; the art and communication symbols of the Orient. One had to recognize the sociological implications.

The screen revealed to us IBM cards feeding through the sensitized plates of the “Electronic Brain,” while from the sound track we heard the actual recording of the sound pulses of this “brain”—pulsations so rhythmic and musical that one was reminded of a Stravinsky symphony. We watched the evolution of calligraphy from hieroglyphs. We saw a beautifully designed “cartoon” in which there were no characters, but only sound symbols, drawn. And we saw on one side screen a slide of the hand of God (a detail from the Michelangelo fresco), while on the other side screen was a slide of a page from the Bible, with the quotation, “God made man”; and after a moment’s delay, the center screen showed a cover from COLLIERS magazine, This particular portion gave different ideas to various people who saw it. But when one remembers that the theme of the entire demonstration was “communications”, he realizes the full impact of the analogy.”

“…We had projected before us a color slide showing a distant view of a cathedral of ancient Europe. As the slides increased in scale and the accompanying music increased in tempo, we moved closer and closer to the cathedral. Shortly we wore confronted, on three screens, with the details of the doorways. As we viewed these details, we realized that we were looking at what might be not only the front of the cathedral but the sides as well. The music faded, and a voice came over the microphone, referring to the significance of Gothic architecture, its reason for being, and our reasons for appreciating it. Possibly fifteen seconds elapsed before we “entered” the cathedral. Light fanned in from its windows, and once more we had the feeling that we were inside this ancient edifice. The scale was there, the atmosphere had been created, and we were even conscious of the incense— it had been carefully prepared and blown through the room by means of fans.

It was interesting to record the reactions. Some saw the Eames-Nelson exhibit once, some saw it three or four times.

Someone in the field of theology, “saw parallels in the way he presented information, so it was with a professor of Physics, and Economics, and with many others.”

One audience member claimed, “This might very well be the turning point in educational procedures”.

Another said, “I feel that I was most fortunate in being among those present at this event which is, I am sure, the most valuable contribution to Art Education in recent years. It is the beginning of a movement or idea that should bring art experiences into our daily living and teaching as a vital and indispensable force”.

“It was a thrilling experience, and opened such vast fields for future effort that we are all very curious to know where the program goes from here,” claimed another audience member.