There are four domains that overlap in this research: art, education, technology, and industry. Concurrently, five different storylines all converge in the 1952 Art X demonstration. These storylines include the creation of visual art department at the University of Georgia, the career of the artist Lamar Dodd, the career of the designer George Nelson, the career of designer Charles Eames, and the career of educator Hoyt Sherman. The landscape of these stories includes the cultural events of the United States between the 1940’s and 1970’s. George Nelson wrote an account of his “very personal involvement with the very large problem of teaching in a University” in an essay he titled, “The Georgia Experiment.”

The academic discussion of the Georgia Experiment often begins with an event that occurred six years later, the 1959 National Exhibit in Moscow. This cultural trade exhibition displayed the methods of the Georgia Experiment on a world stage and used them to inform a skeptical Russian audience. The designers needed to share with America’s rival, the Soviet Union, and hopefully prove that America’s way of life were worth living. One of the men who would make the journey to Sokolniki Park in Moscow was an artist named Lamar Dodd, who had been increasingly called to act as an unofficial ambassador and curator of American culture.

In 1955, Lamar Dodd was one of the most influential art scholars in the United States; the artist was at the height of his fame. Among his responsibilities, the Carnegie foundation charged him with supervising a slide survey of visual art from the United States of America. He even had a household name thanks to a Life Magazine story in 1949, and in 1953 he would become President of the College Art Association. A year earlier Dodd hired George Nelson to improve his school’s art department; the meeting would come at the height of Nelson’s own fame.

For his part, George Nelson was one of the most influential designer theorists in the world. He had made name for himself by winning the Rome prize and spending his time in Europe interviewing the modern architects who would become household names: Mies Van der Rohe, Le Corbusier, and even Mussolini’s Piacentini. As the head of Herman Miller, Nelson commanded a powerful industrial design company, and as a writer Nelson would critique everything from national education practices, to what he saw as an increasingly materialistic world culture and what he called the end of “architecture.” At Herman Miller he quadrupled the earnings of a nearly bankrupt cabinet shop giving it a two million dollar profit in just one year. He explained his success by a tendency to surround himself with genius, among which company he included Charles Eames.

Charles Eames, along with his wife Ray Kaiser Eames, would become synonymous with modern design. They had their start designing plywood chairs for the masses and through the course of their lives ended up inventing new film techniques, planning a design school for the Indian government, and helping producing the first multimedia presentation ever recorded. They had a special design philosophy, “the best for the most for the least” that would spill over into almost every form of communication, even those that had yet to be fully invented. In the course of his first collaboration with George Nelson, they devised a method, which simultaneously projects a program on 3 screens. This method would allow them to transport a Cinerama experience across the country and expose the connections between multiple concepts.

At the same time, an artist and Professor at Ohio State University, named Hoyt Sherman experimented with multiple screens for teaching. Sherman’s life’s work was in teaching and his students remain his legacy. His student Roy Lichtenstein credits Sherman’s theories with aiding own artistic development. Despite relative anonymity, Sherman published a book called, Drawing by Seeing which caused controversy with its avant-garde theories. Betty Edwards the popular author of, Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain credits Sherman with establishing a psychological groundwork for her own methods. Sherman’s masterpiece was what came to be known as the “The Flash Lab.” This was laboratory space that combined a drawing studio with an ophthalmology laboratory in a particular way. Sherman discovered, with the help of noted Ophthalmologist Adelbert Ames, that his program of drawing exercises improved the eyesight and visual awareness of his test subject students. His use of gestalt principles and scientific experimentation to the world of fine arts was met with substantial criticism despite its demonstrated effectiveness.

The art world and the teaching of art in the academies of the United States were both transforming dramatically during this period. The United States, itself, was still transforming dramatically and in the post-World War II era there were more and more students looking for higher education. The University of Georgia existed a full century without establishing any formal art classes. By 1920, however, the allegedly “female” pursuit of studying art was beginning to lose its local stigma. In 1927, the board of trustees of UGA established a board of fine arts within the largest school, The College of Agriculture. Hugh Hodgson was recruited to start the music program, which immediately brought national prestige to the study of fine arts in the south. With some pressure from the students who managed to raise a couple hundred dollars all by themselves, the school was further inclined to address the issue of a visual arts program. Pinpointing the exact beginning of the department of visual art at Georgia is rather complicated. There were various attempts at teaching art organized by various schools in and outside of Athens, Georgia. It is generally accepted that the school really became truly unified when Lamar Dodd was appointed the head of the art department in 1938.

ARTSOUTH EXPANDS

The Fine Arts department became an instant source of pride for Georgia boasting in 1941 a brand new Fine Arts Building, which could seat 1,500 people in its auditorium. By 1945, Dodd would convince a private collector, Alfred Holbrook to donate his 100 paintings to found the Georgia Museum of Art. In these early days, the fine arts department, the museum, and the library would all end up sharing spaces and purposes; huddled as they were on North Campus where the oldest buildings modeled after Yale’s Connecticut Hall still stand today.

This new department was one of the most popular on campus, and money from national grants ensured it had some of the largest budgets. New disciplines of study were added to the program and more faculty positions. There were also more graduate students, and art majors than could comfortably fit inside their classrooms. The art school overflowed with students; instructors bravely taught their lessons in unfinished rooms. They developed slides in photography laboratories that had no running water. These issues hardly compared to the stifling heat inside of the building. Yet, a sense of pride accompanied these hardships, a “pioneer spirit” which the teachers embraced. Dodd continued pushing the boundaries of his program and the nerve of his community; he even hired experts to critique their teaching methods.

Naturally construction on campus stagnated at Universities across the country during World War II. Despite the troubles abroad a compromised version the Fine Arts Building was finished in 1941 and celebrated with a five day festival of plays, music, and art. This inauguration felt like an injection of culture and this affirmative act helped convince the Rockefeller Foundation’s General Education Board to expand the school. That summer the university provided art history courses for educators and expanded their course offerings to include more photography and commercial art courses. Most of all GEB dollars would buy crucially needed supplies and equipment. These successes led to a quantum leap forward in endowment, starting in 1952 the General Education Board would provide $250,000 over eight years. With these funds major new plans could be drafted and carried out with confident authority.

The Art X demonstration was first conceived as a report on teaching efficiency and in addition to this advisory lesson there were lectures by Fuller, Nelson, and Eames among others. The plan that was presented to UGA by its art department included art history classes more graduate students, a new design program, new buildings, and an experimental new curriculum.

Ohio State University’s Frank Roos Jr. wrote an article for Parnassus Magazine in 1940 about the University of Georgia. The connection between these schools was crucial to Georgia’s art department in the formative years. More than a few OSU alums were hired to fill the ranks of their program among them was Erwin Breithaupt. While Roos would claim that the UGA’s art department began in 1937 when Lamar Dodd arrived on campus, the truth is that it began a decade earlier. It would take these ten years for the loose collection of classes taught for the benefit of various schools to coalesce into a program befitting an institution of higher education. The difference was between students studying art as a hobby and studying to become professional artists. By 1940, Dodd’s program was one of the most popular on campus.

The original four concentrations for Bachelor of Fine Arts students were: art education, commercial art, design and crafts, and drawing and painting. These contrast with the more technically specific equivalents that are used today; art education is still offered but now so is art history. There is today a graphic design concentration, as well as interior design, fabric design, photography, jewelry and metal working, sculpture, printmaking and a digital media discipline called, Art X.

Roos pins down the beginnings of the UGA art department beginning in 1937, when it immediately became one of the largest on campus by enrollment. Roos’ essay in the magazine Parnassus is from Ohio State. His connection combined with the Flash Room concept begs the question how did the relationship between Ohio State and The University of Georgia really begin. The obvious connection is that Lamar Dodd in his student days helped make the connection that would tie the schools together afterward. The art education community of the United States is in some senses a small world. A recurring theme in the UGA’s art department’s youth was a “pitch in” attitude. Teachers would donate their service to worthy causes and local workers would buy paintings from traveling exhibitions for the express purpose of donating it to the new Museum.

All the fine arts including music and drama departments were deliberately placed in the same building to facilitate cross pollination. At the same time all the departments had access to the spacious theatre as a venue for public seminars and eventually the Eames-Nelson Demonstration which blurred the line between visual art and theatre. Ray Kaiser considered Art X a work of art, itself.

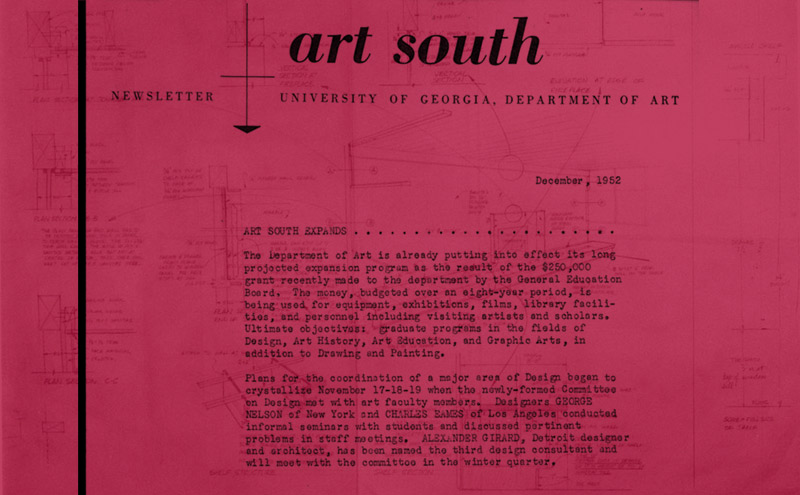

A flier dated December of 1952, an art school newsletter, shed some light on the perspective on the program from the staff. The announcement of the 250,000 dollars awarded the school was explained to the public: “The money, budgeted over an eight year period, is being used for equipment, exhibitions, films, library facilities, and personnel including visiting artists and scholars.” Documents in the academic reports from these years explain Art X as a part of their plan to create new graduate programs, but this point was easily lost among the other daily issues and appeals for physical space.

Ultimate objectives: graduate programs in the fields of Design, Art History, Art Education, and Graphic Arts, in addition to Drawing and Painting.

Plans for the coordination of a major area of Design began to crystallize November 17-18-19 when the newly formed Committee on Design met with art faculty members. Designers George Nelson of New York and Charles Eames of Los Angeles conducted informal seminars with students and discussed pertinent problems in staff meetings. Alexander Girard, Detroit designer and architect, has been named the third design consultant and will meet with the committee in the winter quarter.”

Title image above comes from The University of Georgia, Newsletter.

“Art South Expands,” Art South, (1952).