While Nelson was an unwilling administrator, Charles Eames was a reluctant innovator. His motto was, “Innovate as a last resort,” yet he found a good reason to innovate both industrial design and film. This paradox can be explained by Eames’ motto: Create the best for the most for the least. Charles and his wife Ray Kaiser Eames devoted their lives to the pursuit of bringing the best possible products to people, for the least amount of cost possible. This philosophy combined with their poetic style made them darlings of American Modernist Design. Their experiments in molded plywood gave way to plastic chairs that would seat people around the world. The Eameses were specifically asked to lend their expertise in design to the University of Georgia which wanted to include the subject in their school. This project involved working with Lamar Dodd and his staff, but it would become only the first of many investigations into education for the Eameses. Their very next client was the country of India; who needed a design school that would lead them into the 20th Century overnight. A year after this exhaustive commission, the Eameses would have a reunion with their Art X colleagues in Moscow, for the world’s preeminent multimedia presentation.

Both Charles and Ray Eames acquired educations in a variety of formal and practical ways, they studied: theater, architecture, painting, industrial design, film, photography. What emerged was a style and a philosophy. They preached, “innovate as a last resort” and “the best, to the most, for the least.” But they also believed that one must first: “Know what you are talking about.” As an architect, Charles relished practical problem solving, but hated the committees involved with large building projects so he took up furniture design where he could control all aspects of creation. “Art X” was the opportunity to begin codifying what he had learned by trial and error and by exhaustive life experience.

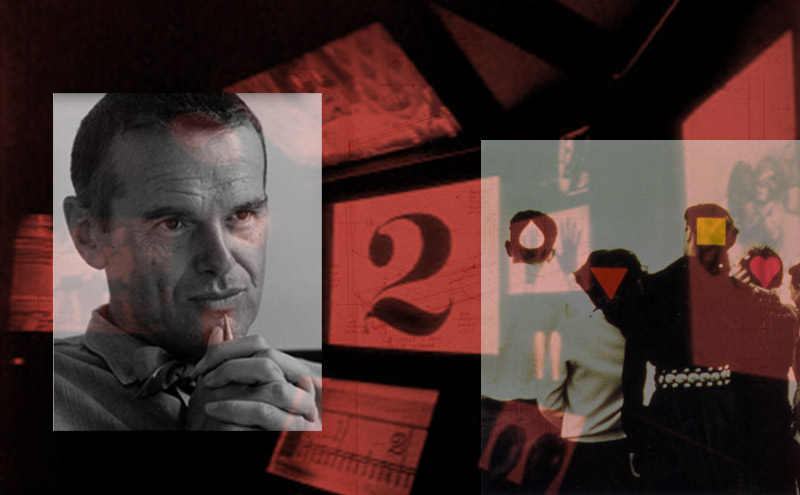

There is so much written about Charles Eames and his famous chairs, but Eames would probably appreciate the succinct way a newspaper gets his lifre down to the essentials in death.

“Chair Designer dies at 71,” announced the Jefferson City Post-Tribune, on August 23, 1978. Private funerals services were held for the architect in St. Louis, he first designed his famous chairs in the late 1930’s, the paper recalls.

“They were too costly to produce until the 1940’s when they perfected an inexpensive molding process in their small Los Angeles apartment. They took turns pedaling a stationary bicycle that pumped the compressed air to bend the plywood... ‘With the earliest pieces, we built all the tooling. We manufactured the first 5,000 chairs right in our office,’ Eames stated in an interview.

Years earlier another newspaper had this to say about Eames, “Famed U.S. Camera Man Will Shoot ‘The Fabulous Fifties.” The article was announcing that Charles Eames was working on a 90 minute show for CBS on January 31 of 1959:

“The tasteful inventive camera work of Charles Eames has brought grace and beauty to every project with which he has been associated.”

“World-wide fame caught up with the U.S. photographic exhibit at the Moscow Fair. He conceived and executed the plan to flash simultaneously seven color photographs of U.S. life including some 2,200 photographs – in the incredible space of 12 minutes.”

“To tell the story of the most dramatic decade in the memory of today’s TV audience demands far more than the simple integration of film shots. The camera must capture not just the particulars but the universals. It must record not merely what happened – in the areas of art, science, entertainment, and everyday living – but the feeling of what these events have meant to the people.”

The contemporary world mostly remembers this much of Eames’ life and work: chairs and film making in the fifties. There was a common philosophy invested in both of these labors, one that he codified in his lectures and in his work for a hypothetical course. Art X was as much a philosophy as a film technique. Moving pictures, either in film or slideshows were the way he communicated and the method of communication he thought would be used to teach in the future.

According to Esther McCoy, in her book “The Design Process at Herman Miller: Charles and Ray Eames,” Design Quarterly their films began as means of recording furniture design and exhibitions, the accession of toys, folk art or circus memorabilia: however the introduction of multimedia techniques as fast cutting, ellipses, and surprise juxtaposition raised film making to a very personal art.

From the first multimedia expression, “A Sample Lesson” in collaboration with George Nelson and Alexander Girard new visual areas were explored for communicating complex information and by nineteen sixty two when the Eameses made POWERS OF TEN they had a acquired a sharpness and economy which make their visual metaphors accessible.

They had had what hey called “information films” and “object films,” but their love of narrating facts blurs the distinction.

Eames made films and sideshows all the time, sometimes as a means to convey a plan to their coworkers in their workshop, sometimes to their future clients, and sometimes as works unto themselves. Charles would construct his own lens and incorporate his still photography so that they would have the control so ahead of its time. They thoroughly explored the possibilities of projection, experimenting with different configurations and scales. They designed films for their government, for students, and for future teachers.

According to Pat Kirkham, one of Charles’ biographers, in 1960, 125 to 200 motion pictures were being made per year at the cost of $1,000 per minute for black-and-white films. 10 minute films might be made for as little as $7,000 for as much as $70,000. The Eames style was to only take commissions in which they had substantial creative freedom, and ended up working for Herman Miller, IBM, they went on to produce for Westinghouse, ABC, Boeing, and Polaroid.

Kirkham like many researchers calls, A Rough Sketch for a Sample Lesson for a Hypothetical Course “the first public multi-media presentation in the United States, delivered in 1953”

The aim of the film was to replace the conventional lecture.

“We used a lot of sound, sometimes carried to a very high volume so you would actually feel the vibrations… We did it because we wanted to heighten awareness…The smells were quite effective. They did two things: they came on cue, and they heightened the illusion. It was quite interesting because in some scenes that didn’t have smell cues, but only smell suggestions in the script, a few people felt they had smelled things- for example, the oil in the machinery.”

The method prioritized developing creative capacity through the understanding ideas and concepts, at the expense of extraneous details.

Eames seemed especially skeptical of the almost mythical teacher-student relationship, which supposedly contained intimacy and sensitivity individual needs. Eames acknowledged that the best teachers are able to convey information well through lectures. His conclusion was to reward these talented teachers by putting them into the driver’s seat, and removing less talented teachers altogether.

Eames assertion that art teachers are often the problem with art schools was controversial.He made believers of the staff, but the general consensus was that his method was too complex and too expensive. (It had taken 8 people to operate his demonstration.)

Paul Schraeder's interview for “Poetry of Ideas: The Films of Charles Eames,” Film Quarterly, Vol.23, No.3: in 1970 provides a useful glimpse of Eames thought process.

“Still, putting an idea on film provides the ideal discipline for whittling that idea down to size.”

“I don’t really believe we overload, but if that is what it is, we try to use it in a way that heightens the reality to only a sampling, that sampling will be true to the spirit of the subject. Maybe after seeing one or two, the viewer learns to relax.”

There films are either the logical extension of their problem at hand, or it is the result of a long considered problem that can’t be put off any longer.

Michael Brawne wrote in Architectural Digest that the method of film making is relatively simple to produce and that more information can be conveyed than when motion is represented on screen, and this corresponds with the way the brain normally records images. Charles Eames said this:

“Because the viewer is being led at the cutter’s pace, it can, over a long period, be exhausting. But this technique can deliver a great amount of information in much the same way we naturally perceive it- we did this pretty consciously.”

Fiction for the Eames films really means, simulation, and no semblance of plot, they replace plot with structure. They try to reduce a problem to a series of small simple units that even the audience could really understand and therefore pass something on of this understanding. Some special combination of units may give the whole piece a smell of science or of philosophy.

To Charles “polarized training” is dangerous, and feels especially unnecessary now. This polarization is response to C.P. Snow’s “Two Cultures” which argues that Art and Science are two distinct spheres.

Additionally, Charles stated “we have fallen for the illusion that film is a perfectly controlled medium, when it is in the can, nothing can erode it, the image, the color, the timing, the sound, everything is under control, it is just an illusion- thoughtless reproduction, projection, presentation turn it into a mess again. This recalls Thelma Schoonmaker’s observation that a film’s final editor is the projectionist.

Eames began a lifelong work of teaching first through example, then in a concerted way with his relationship with the University of Georgia. He continued this work through his many lectures both around the country and in his own backyard at UCLA.

However, perhaps the most complete vision of Eames ideal teaching environment came in India. At the request of the Indian Government, Eames drafted a report. This report like the one at UGA became more exhaustive than anyone likely imagined.

Eames believed that proper design could, should, and would help solve the world’s problems. Its been theorized by various journalists that growing up in the nineteen thirties in America instilled in Eames his feeling that the most should be done for the least. His personal ethic of rejecting worldly materialism complemented the Bhagavad Gita nicely.

To Eames, the birth of industrial design coincided with an almost immediate deterioration of quality in goods. Mass production was a double edged sword. Meanwhile, a dramatic acceleration in a culture could cause rapid deterioration of “standard of living.”

The task of his report was to design a program of design education for India. Charles and Ray realized that it would take an exhaustive yet priceless study of the entire culture: its philosophy, its geography, as well as “sociology, engineering, physics, psychology, history, painting, [and] anthropology,” anything to restate questions of familiar problems in a fresh clear way. They recommended that the committee be a part of ministry of commerce, but retain autonomy, with a board of governors from the fields mentioned above.

They believed that communication is something that affects a world not a country. Likewise, education is a impossible to improve without addressing all the components on every level. This is Charles Eames legacy to education: a body of film work which can continue to serve as a example and a thorough example of how to address all aspects of the design problem that is education.