Following a series of demonstrations in Athens there was a public request for repeat performances in other parts of the country. The University of California in Los Angeles teamed up with a few local institutions to subsidize another showing of Art X. Next there would be a showing in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, as well. Everywhere that the Art X experiment was shown, its audience was spellbound by the experience. Later, the Eameses edited together their various film segments into a movie called, “A Communications Primer.” This film would continue to open doors for them, including a long running relationship with IBM, to produce films with similar subject matter. Nelson documented his own perspective in an essay about the Advisory Committee’s work and dubbed the whole episode, “The Georgia Experiment.” Back in Athens, the Secretary and Chairman of the Fine arts committee of Harvard University visited the University of Georgia with the purpose of emulating their methods in their own art department.

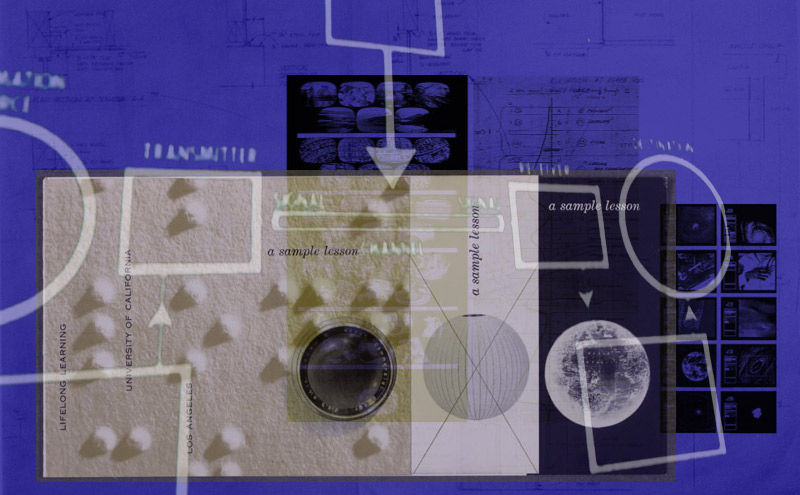

“Art X,” “Georgia Experiment,” “A Sample Lesson for a Hypothetical Course," for the demonstration of a teaching procedure. The names were attributed after the fact; a snowball effect continued, adding to this project even after it was expected to conclude. The interest and publicity were great enough that the the “Art X” show would be requested at different schools around the country.

We know that Charles Eames took an active role in reproducing the Georgia Experiment he was called to bring the production in California then in Pennsylvania. Nelson would continue to use a version of three screen, himself, throughout his lecture career; meanwhile UGA would include the Art X example as a plan for its new curriculum.

Dodd would cite the demonstration as a means of fufilling an “interdisciplinary” art program. Meanwhile, Erwin Breithaupt would document their work at conferences and in published essays. The various schools and programs that worked together to bring Art X to the University of California is notable, in itself. The team included UCLA’s Faculty of Engineers and California’s Board of Education. This project of a report on art teaching methods at UGA would lead Charles Eames naturally into his famous "idea films". Ray Eames would later talk about their plan for introducing architecture in primary schools as an extension of this way of thinking. The Eames Report, a plan for India’s first design school, is the complimentary piece to the Hypothetical Lesson, The Georgia Experiment demonstrated a hypothetical lesson while the Eames Report designed a hypothetical school’s infrastructure.

We know for certain there was a precedent in Art X for the Moscow Exhibition, but the idea of an education tool called an information machine was something Eames never stopped investigating. They even named an exhibition in Seattle, “The Information Machine” which later became a permanent installation.

George Nelson’s colleague Buckminster Fuller wrote the book Education Automation including many of their shared views. Nelson also influenced the next generation of designers through an aggressive schedule of conferences and writing, even television broadcasts. There is little documentation available of the correspondence between schools, but the academic annual reports state that schools from around the country requested information about Art X well into the sixties. All the major players of the Art X show: Dodd, Eames, and Nelson would continue referencing their collaboration throughout their lecture careers.

In 1980, Ruth Bowman recorded an interview with Ray Kaiser Eames in Venice, California for the Archives of American Art of the Smithsonian Institution. This interview provides a useful glimpse of how the Art X show proceeded after its debut.

On the subject of the Art X Ray Eames had this to say:

“It was a way of studying the problem. We were asked to do a thing about the Georgia Experiment; did you know about that? How to improve the teaching of design, and art, really, it was art. George Nelson and ourselves were involved and, instead of making a report, we made a film. Or rather, we put together an hour program made up of film and slides and words and clips of other films. It was intended as an example of how material could be used to give a base for student and teacher from which to develop and expand -- not use up all the time, step by step, all of the teacher's time and the student's time. And that was shown. But we wanted examples. For instance, we chose the subject of communications, because we were all interested in that and thought we would find little clips of things that would explain it and help it. We couldn't find any. We had just a terrible waste of time looking at catalogues, trying to find films and finding that it took forty-five minutes to get to a point which was not made clearly. So that's when we decided we'd have to do something ourselves. And then later, Alexander Girard was called in and put on this -- did you ever hear of the "Sample Lesson?" It was shown first in Georgia, then at U.C.L.A. You know, it's like a club, the people who have seen it and the people who haven't seen it.”

Here is a critical excerpt mentioning UCLA staff:

RUTH BOWMAN: The presentation. They were done in the mid-Fifties?

RAY KAISER EAMES: 1952, I think, under the School of Engineering. It was Dean Boelter at that time. He was a friend, such a wonderful man, terribly interested in so many facets of learning. We thought he was great. He enjoyed it all, too, and helped very much.

Meanwhile at UGA received an invitation to be only one of six schools in the nation to participate in the “Good Design” exhibition held at the Chicago Merchandise Mart and later at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. UGA’s art department was the only non-professional school among those selected.

“Our entry, called, “The Story of a Room” a kiosk depicting our basic course curriculum and the teaching methods employed, was viewed by an estimated half-million people.” According to Breithaupt.

Covering the exhibition Aline Loucheim Saarinen, of the New York Times, wrote this in March of 1955:

“In these displays (an adjunct of the fifth anniversary of “Good Design” exhibitions) each of the six schools was invited to present visually the attitudes and problems—the philosophy, if you will—with which its students are being indoctrinated If upbringing has any influence, we can expect competent craftsmen of the machine age. And very little slick trick gadgetry… All this supports the feeling that perhaps the most exciting suggestion for the design of the future lies in the exhibition from the University of Georgia. For here there is interest in a real training in visual awareness not only potential designers but for potential consumers as well.”

In 1954-55 the Secretary and the Chairman of the Fine Arts Committee of Harvard University each visited the department for the purpose of studying UGA’s program and requesting recommendations for use by their committee.

The magazine, Graphic Design Director, in reference to UGA’s design program stated: “…Most professional schools would be more than proud to have this calibre of work in the students.”

Additionally, paintings by four graduate students were chosen that year by a national jury for inclusion in the U.S.I.A. traveling exhibition for European countries. Of the 240 schools contacted, UGA was one of eight finally selected and was the only representative of the Southern States.

There were many national services provided by the UGA staff including: sitting on the Fulbright Committee of Selection, participation in the Department of State’s Cultural Exchange programs, travel to other countries as consultants for IES, USIS, and USIA programs; graphically depicting Astronaut Cooper’s orbital flight for NASA, counseling for the Cooperative Educational Television Board in the Visual Arts for the Voice of America.

Six of the fifteen faculty members from the time of the Art X show remained for fifteen years or longer despite numerous offers from other leading institutions and from industries because there was such pride and interest in the program.

The direction according to Dodd in 1937 was toward developing the creative powers of individuals through the use of their best tools, i.e. their own creativity and creative productivity; through assistance from the GEB grant, toward broadening the concentration and creating a more thorough approach to an advanced curriculum.